The skin–the interface between humans and their environmentais the largest organ in the body. It weighs an average of 4 kg and covers an area of 2 m 2 . It acts as a barrier, protecting the body from harsh external conditions and preventing the loss of important body constituents, especially water. A death from destruction of skin, as in a burn, or in toxic epidermal necrolysis, and the misery of unpleasant acne, remind us of its many important functions, which range from the vital to the cosmetic.

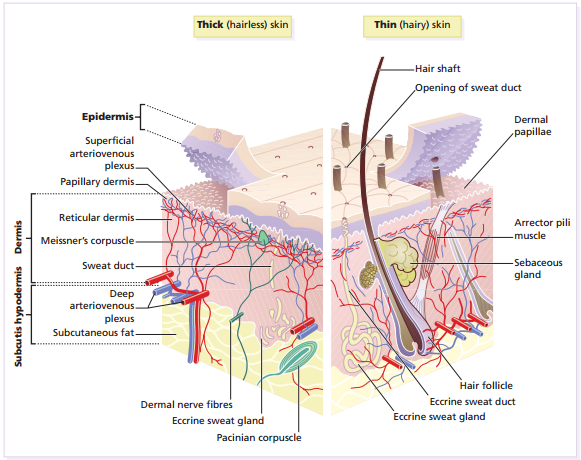

The skin has two layers. The outer is epithelial, the epidermis, which is firmly attached to, and supported by connective tissue in the underlying dermis. Beneath the dermis is loose connective tissue, the subcutis/hypodermiswhich usually contains abundant fat.

Epidermis The epidermis is formed from many layers of closely packed cells, the most superficial of which are flattened and filled with keratins; it is therefore a stratified squamous epithelium. It adheres to the dermis partly by the interlocking of its downward projections (epidermal ridgesor pegs) with upward projections of the dermis (dermal papillae).

The epidermis contains no blood vessels. It varies in thickness from less than 0.1 mm on the eyelids to nearly 1 mm on the palms and soles. As dead surface squames are shed (accounting for some of the dust in our houses), the thickness is kept constant by cells dividing in the deepest (basalor germinative) layer.

A generated cell moves, or is pushed by underlying mitotic activity, to the surface, passing through the prickleand granular cell layersbefore dying in the horny layer. The journey from the basal layer to the surface (epidermal turnover or transit time) takes about 60 days. During this time the appearance of the cell changes.

A vertical section through the epidermis summarizes the life history of a single epidermal cell. The basal layer, the deepest layer, rests on a basement membrane,which attaches it to the dermis. It is a single layer of columnar cells, whose basal surface sprout many fine processes and hemidesmosomes, anchoring them to the lamina densa of the basement membrane. In normal skin some 30% of basal cells are preparing for division (growth fraction). Following mitosis, a cell enters the G 1 phase, synthesizes RNA and protein, and grows in size . Later, when the cell is triggered to divide, DNA is synthesized (S phase) and chromosomal DNA is replicated.

A short postsynthetic (G 2 ) phase of further growth occurs before mitosis (M). DNA synthesis continues through the S and G2 phases, but not during mitosis. The G 1 phase is then repeated, and one of the daughter cells moves into the suprabasal layer. It then differentiates , having lost the capacity to divide, and synthesizes keratins. Some basal cells remain inactive in a so-called G 0 phase but may re-enter the cycle and resume proliferation. The of the arrector pili muscle but cannot be identified by histology. These cells divide infrequently, but can generate new proliferative cells in the epidermis and hair follicle in response to damage.