The disorders grouped under this heading are the most common skin conditions seen by family doctors, and make up some 20% of all new patients referred to our clinics.

The disorders grouped under this heading are the most common skin conditions seen by family doctors, and make up some 20% of all new patients referred to our clinics.

Terminology The word ‘eczema’ comes from the Greek for ‘boiling’ aa reference to the tiny vesicles (bubbles) that are often seen in the early acute stages of the disorder, but less often in its later chronic stages.

‘Dermatitis’ means inflammation of the skin and is therefore, strictly speaking, a broader term than eczemaawhich is just one of several possible types of skin inflammation. In the past too much time has been devoted to trying to distinguish between these two terms.

To us, they mean the same thing. This approach is now used by most dermatologists, although many stick to the term eczema when talking to patients for whom ‘dermatitis’ may carry industrial and compensation overtones, which can stir up unnecessary legal battles.

In this book contact eczema is the same as contact dermatitis; seborrhoeic eczema the same as seborrhoeic dermatitis, etc. Classification of eczema This is a messy legacy from a time when little was known about the subject. As a result, some terms are based on the appearance of lesions, e.g. discoid eczema and hyperkeratotic eczema, while others reflect outmoded or unproven theories of causation, e.g. infective eczema and seborrhoeic eczema.

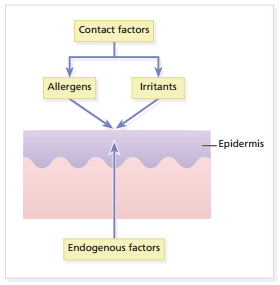

Classification by site, e.g. flexural eczema and hand eczema, is equally unhelpful. Eczema is a reaction pattern. Many different stimuli can make the skin react in the same way, and several of these may be in action at the same time. This can make it hard to be sure which type of eczema is present; and even experienced dermatologists admit that they can only classify some two-thirds of the cases they see.

To complicate matters further, the physical signs that make up eczema, although limited, can be jumbled together in an infinite number of ways, so that no two cases look alike.